The discussion of “cancel culture” and historical monuments highlights the ongoing debate over the removal or reuse of controversial symbols. Examples include the General Lee statue in Charlottesville, Va, and the Monument to Victory in Bolzano, Italy. Alessandro Manzoni’s reflections and romantic irony illustrate how the violent removals of statues and monuments are not new. They are part of a long history of social discourse. He urges a nuanced understanding of the past rather than simple erasure. This approach is at the core of the recontextualization of the Monument to Victory undertaken through the permanent exhibition within the monument to Victory, BZ ’18-’45 one monument, one city, two dictatorships. In the post’s Conclusion, the perspective of geological time represented by the Bletterbach “natural monument” is introduced. This perspective, as the one implied by the permanent exhibition, relativizes the historical values considered absolute.

Cancel Culture and Alessandro Manzoni’s reflections on the fate of statues

One of the most discussed topics of our time is the attitude toward the controversial past. Since the “Cancel Culture” was born in the United States more or less in the last decade, the news is full of episodes in which statues of disputed historical figures from the past are removed, replaced, or destroyed. The latest episode I read today in the New York Times is that of General Robert E. Lee, best known as the Confederate States Army commander. In an opinion guest essay entitled The Most Controversial Statue in America Surrenders to the Furnace, Erin Thompson describes the last moments of the statue that had gazed down on Charlottesville, Va. The statue stood from atop a massive horse from 1924 when it was installed until 2021, when it was removed by the City Council. In 2023, the foundry workers cut the monument into pieces small enough to fit into the furnace for melting it. “Melting Lee down and turning him into something new is a violent act and also a hopeful one,” Thompson writes. He suggests that the metal obtained from the fusion of the Lee statue could be used to create new artistic forms. These forms would serve as an expression of democratic values. He also reminds us that episodes like this are part of American history. One of the first metal monuments arrived in the American colonies, a gilded lead statue of George III. It was melted down in 1776 to make ammunition for the fight for democracy.

The violent erasure of the monumental culture of the controversial past is, therefore, not a recent and not necessarily American fact. One would be tempted to say it is as old as human civilization. Still, it is possible to locate the emergence of phenomena similar to those we witness today in eighteenth-century Europe and the French Revolution. In this regard, a historical episode from Milan, told by Alessandro Manzoni in chapter XII of The Betrothed, comes to mind. In this chapter, we read the story of the revolt of the seventeenth-century Milanese masses against the increase in the price of bread. The revolt led to the consequent assault on the bakeries. In this context, Manzoni recounts how, at times, the gaze of the rioting people focused on the statue of Philip II, King of Spain, who governed the Duchy of Milan. The writer’s comment reveals a deep knowledge of the psychology of the masses and the mechanisms of political power:

“The scowling face of King Philip II, even from the marble, imposed a mysterious respect, with his arm held out as if to say: ‘I’ll come and see to you in a minute, you miserable rabble!” (173)

The writer here captures with subtle irony the purpose for which the statue was created and placed in Merchants’ Square. It had to intimidate the people by imposing a panoptic gaze that demanded unconditional respect and obedience. The romantic irony of the writer is not satisfied with this lucid observation. He accompanies the reader in a digression on the fate of that statue of one of the foremost exponents of monarchical absolutism. In this way, he introduces into his novel set in the seventeenth century the very different perspective of the following century. This century is characterized by the Enlightenment philosophies and the revolutionary climate that wanted to undermine the absolutist system in Europe.

He writes,

“That statue is not there today, and the explanation is a strange one. About one hundred and sixty years after the events we are describing, they gave His Majesty a new head, put a dagger in his hand instead of a sceptre, and rechristened him Marcus Brutus. The statue remained there in its renovated form for a year or so. But one morning some people who were no friends of Marcus Brutus, and in fact must have had a secret grudge against him, put a rope round the statue, pulled it over, and subjected it to all kinds of indignities. They mutilated it and reduced it to a formless torso; they pulled it through the streets, their eyes starting from their heads and their tongues lolling from their mouths; and when they were completely exhausted, they dumped it somewhere – I cannot say where. How surprised Andrea Biffi, the sculptor, would have been if he had known all this while he was carving the statue!” (173-174)

Manzoni refers to the year 1797, when Napoleon conquered Milan. The statue of Philip II, a symbol of absolutism and authoritarian government, was violently transformed into Marcus Brutus. Marcus Brutus was the tyrannicidal killer of Julius Caesar, a dramatic symbol of republican freedom after the French Revolution. But after the Restoration and the return of the Austrians, the new image of the statue was tampered with. It was also violently destroyed. In this way, Manzoni’s story compares the crowds that rebelled against the Spanish governor in seventeenth-century Spain. He contrasts them to the opposite republican and conservative crowds of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, respectively. These crowds destroyed the symbols of power in the name of the Enlightenment or the Restoration. Manzoni’s point in this excursion is that the characters of Philip II and Brutus are similar in their pride. They are also similar in their criminal violence. The irony of his novel includes and comprehends this violence and its social roots. It ultimately rejects it and the extremists that disguise themselves in heroic clothes. Manzoni’s irony expresses itself with a light touch and a puzzled smile.

In Manzoni’s story, we find some ideas that are also interesting to us. They also contribute to the reflections that loom in our current time. The acute psychological observation on the communicative effectiveness of the statue of Philip II is worthy of note. It spreads the social subjection of the marginalized masses excluded from history. After all, centuries later, the statue of Robert E. Lee had to serve the same purpose. This is evident if we pay attention to the words of a Charlottesville high school student, Zyahna Bryant, reported in Thompson’s article. She petitioned to remove the monument and declared, “I am offended every time I pass it… I am reminded over and over again of the pain of my ancestors.” That petition began the journey that brought Lee’s statue to the melting pot. Thompson reminds us that more than a hundred Confederate monuments were taken away from their pedestals. This occurred during our USA’s recent racial reckoning following the killing of George Floyd. The emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement played a role as well.

He laments that there is no longer vital public attention to these issues. There is no consensus on what to do with these controversial monuments of the past. Many oppose the destructive violence of “cancel culture.” They suggest reinstalling these artifacts by placing them in a museum context. In the museum, their disputable historical meaning can be recognized, discussed, put into historical perspective, and eventually rejected. Thompson does not support this “compromise” solution. He prefers more radical options of high symbolic value. These options include the melting and repurposing of the statues. This action reverses with equal violence and effectiveness the symbolic value for which those statues were built: “Confederate monuments went up with rich, emotional ceremonies that created historical memory and solidified group identity. The way we remove them should be just as emotional, striking, and memorable. Instead of quietly tucking statues away, we can use monuments one final time to bind ourselves together into new communities.”

Thompson’s argument is powerful but not as reflective and complex as the one implied in Manzoni’s ethical and ironic narrative. At the heart of Manzoni’s irony about the historical plausibility of canceling the icons of the past, even when these traces are highly questionable and in apparent contradiction with the present values, is the idea that cancellation interrupts the conversation and reciprocal nourishment between the present and the past. For him, the practice of canceling the past reinforces an intolerant culture primarily based on cognitive biases: a polarized culture where the opposing parties are not interested in reasoning and dialogue but only in looking for evidence of what they already think. When one looks only for information confirming one’s beliefs, one loses the ability to scrutinize the past and its complexities. On the contrary, Manzoni’s ironic gaze comprehended all perspectives. These included the conservative government and the revolutionary people with their drive to destroy the symbols of oppressive political powers. It also included the statue itself and the artist who created it. This approach helps us to critically understand the historical events he was recounting. The destruction of the statue or its substitution with another one with an opposing symbolic value does nothing but promote dogmatism and close-mindedness. It leaves no room for the narrative and philosophical irony so dear to Alessandro Manzoni that we already explored in another post on this blog, Contagion, ethics, and compassion.

Understanding and Overcoming Cancel Culture: The Monument to Victory in Bolzano

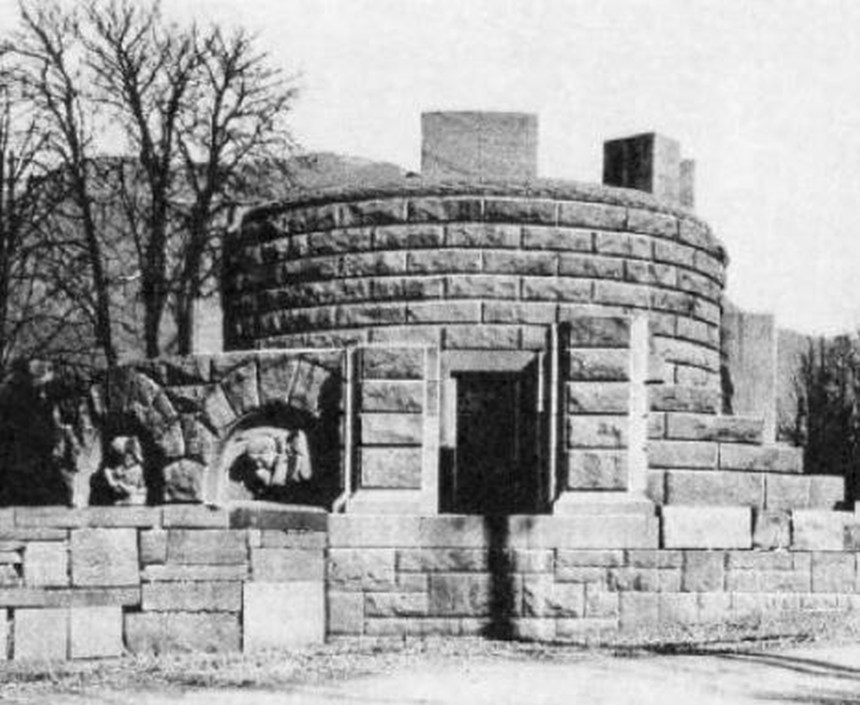

Manzoni understands the violence of the people fighting for social and economic justice. By representing it, he confers and confirms historical plausibility. On the other hand, he adds another layer to the historical narration’s immediacy and realism. He creates a distance from the narrated event through irony and philosophical reflection. The move from representation to reflection creates a frame. In this frame, the seventeenth-century episode of canceling culture is seen at a different level. Manzoni today would support a critical attitude towards the past based on contextual historical and philosophical understanding. An example of this approach in the present time can be seen in the re-contextualization of the Monument to Victory in Bolzano (Bozen). The Victory Monument (Italian: Monumento alla Vittoria; German: Siegesdenkmal) is a monument in Bolzano erected by the Italian Fascist regime in South Tyrol, which had been annexed to Italy from Austria after World War I. The 19-meter-wide Victory Monument was designed by architect Marcello Piacentini and substituted the former Austrian Kaiserjäger monument. The Austrian government started to build the Kaiserjäger monument to the Bolzano fallen in WW1 in 1917, but the construction was interrupted by the defeat of the Austria-Hungary empire in WW1. The Fascist regime turned down the Austrian monument in 1926-27 and started the construction of the Monument to Victory in Fascist style, displaying lictorial pillars. It was dedicated to the “Italian Martyrs of World War I.” Still, more than a commemorative monument, it recalls the Roman triumphal arch as it was meant to celebrate the victory of the Italian army over Austria-Hungary. It asserts not only the Italinaty of the newly acquired territory, the Tyrol, which had a majority of the German-speaking population, but also the “superiority” of Italian civilization as opposed to its Northern European neighbors.

The new memorial was inaugurated in September 1928. Since then, it has been a source of continuous local division as a powerful expression of Fascist totalitarian ideology and forced Italianization of the South Tyroleans. As Manzoni’s narrative testifies and Thompson’s article confirms, as frequently happens in history, the new government uses some material from the old monument to build monuments with an opposite message. Although most of the Monument to Victory is built with Carrara’s marble, the crypt is built with granite reclaimed from the demolished Austrian Kaiserjäger monument. Interestingly, the crypt does not host tombs but serves as a ceremonial role. It contains two allegorical frescoes: The Custodian of the Fatherland and the Custodian to History. The altar with Libero Andreotti’s sculpture of the risen Christ is directly overhead. The altar commemorates Italian soldiers’ sacrifice and the Fatherland’s rebirth. The Christ figure raising himself up as if ascending from the crypt below becomes an allegory of the resurgence of the Fatherland.

The inscriptions chosen for the Monument to Victory defined it as marking the border and being a sacrificial altar. Nonetheless, they showcase Fascist nationalism as it is evident in the Latin inscription on the main façade: HIC PATRIAE FINES SISTE SIGNA / HINC CETEROS EXCOLVIMVS LINGVA LEGIBVS ARTIBVS (“Here at the border of the fatherland set down the banner. From this point, we educate others with language, law, and culture.” This inscription, asserting the supposed superiority of Italian civilization over that of the northern neighbors, was seen as provocative by many within the German-speaking population in the province of South Tyrol. On the inauguration day, there was a counter-demonstration with 10,000 people in Innsbruck. Since then, this controversial monument has long been the focal point of battles over politics, culture, and regional identity. The other Latin inscription on the memorial says: «IN HONOREM ET MEMORIAM FORTISSIMORUM VIRORUM QUI IUSTIS ARMIS STRENUE PUGNANTES HANC PATRIAM SANGUINE SUO PARAVERUNT» («In honor and memory of the powerful men who strenuously fought with just weapons protected this homeland with their blood»).

The divisive value of the monument persisted and, in some cases, exacerbated over the years, even after the treaties between Italy and Austria in 1947 and then in 1972 granted considerable autonomy to the Tyrol-Alto-Adige and basically established bilingual education in the region. The monument is located in Piazza della Vittoria (Victory Square). To understand its complex nature, a persisting symbol of divisive views of local identity, one should remember that in 2001, it was renamed Piazza della Pace (Friedensplatz; Peace Square). But in 2002, following a consultative referendum, the citizens of Bolzano wanted to restore the square’s original name. Some of the events that followed this decision bear witness to the possibility of an ethical approach to the past, respecting all the differences in a collective memory. The municipal council of Bolzano reintroduced the previous name (Victory Square) but also wanted to place the writing “Già della Pace” (Formerly “Peace Square”) under the toponymic plaque “Piazza della Vittoria”. Moreover, in 2004, the municipal council placed a plaque near the monument that declares: “The City of Bolzano, a free, modern, and democratic town, condemns the discriminations and divisions of the past, as well as all forms of nationalism and pledges its commitment to promoting a culture of fraternity and peace in the true European spirit.”

In 2011, the Italian national government created a scientific committee to address in a “European spirit” the recurrent divisive and hateful episodes triggered by the monument by creating a permanent exhibition in the underground space. The committee comprised members from the government, the Autonomous Province, and the City of Bolzano. The conception of the BZ ’15-’45 Permanent exhibition was the creation of an intervention that explained and historically contextualized the monument, illuminating the totalitarian elements, the celebrative intention, and the historical-artistic values. (DI Michele 11) The committee chaired by the architect Ugo Soragni –a scholar author, among many publications and government tasks for the protection of the Italian artistic and landscape heritage, of a 1991 monograph on the Monument to Victory– developed an exhibition which tells the story of the monument and its ideological meanings following the trajectories of the Fascist and Nazi dictatorships with a special consideration for local history from 1918 to 1945.

BZ ’18-’45 one monument, one city, two dictatorships, the permanent exhibition within the monument to Victory, is not a museum but a space of critical engagement that helps to re-think and re-functionalize this controversial monument into the life of a divided community that wants to find a way of living together in peace. In an interview on the question on how to approach the controversial monuments of the past, Ugo Soragni replied,

“I think that with the distance of many years since those events, the only path available is one o understanding an contextualizng the events that caused injury, or which in some cases continue to cause discomfort today. The destruction of such symbols does have a historical plausibility, when it happens immediately after the historical situation that ends the regimes that imposed them. lt is always like that, with little to add when these acts are carried out after the events that end dictatorial eras. With the passing of time, however, the approach must he more relaxed. Such monuments should be viewed not only as historical documents, but also evaluated for their architectural and artistic value. The only possible way forward is that of studying these objects to understand these matters, to work toward being able to offer explanations to both citizens and scholars” (Soragni 28-29).

Nonetheless, the intervention realized by the permanent exhibition, while preserving the physical integrity of the Monument to Victory, found ways to undermine and reverse its original ideological meaning. One of this way in its irony and simplicity would have appealed to the Romantic irony of Alessandro Manzoni. A LED ring scrolling text running around one of the lictorial columns on the front of the Monument was added; while the rest of the monument’s exterior was left untouched. As Jeffrey Schnapp from Harvard University who collaborated with the scientific committee that created the permanent exhibition writes,

... the ring in question serves as a billboard for BZ ’18-’45 and public address system. But there’s a deeper function, at once aesthetic and symbolic: to unbalance the façade with its neoclassical symmetries–not to mention, the ideology embedded within those neoclassical symmetries–in the name of post-fascist-era balance. The LED ring marks the difference between the totalitarian then of the monument’s construction and a now characterized by cultural pluralism and tolerance (Schnapp 2014).

In other words, the LED ring addresses and neutralizes the Fascist ideology of the monument with lightness and irony.

Another ironic intervention, this time more pensive than light, can be witnessed by the visitors of the crypt adorned with frescoes by Guido Cadorin I mentioned above, the Guardian of the Homeland is on the right, with the Guardian of History on the left. The Latin inscriptions on the walls are representative of the Fascist ideology, quotations from Cicero, “Optima hereditas Gloria virtutis rerumque gestarum” (The most beautiful inheritance is the Glory of virtue and heroic acts” and Horace, “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” (It is sweet and glorious to die for the homeland). For the exibithion the inscriptions in the crypt are superimposed by a laser installation, continuously projecting on the walls other quotations which contest and question the original one. The new quotations include Bertolt Brecht, “Unhappy the land in need of heroes;” Hannah Arendt, “No-one has the right to obey;” and Thomas Paine, “It is the duty of the patriot to protect the country from its government.” In this way, the original meaning and message of the Fascist monument is overturned while at the same time preserving its physical integrity. The laser installation and the writings on the wall do not pretend to substitute one monument with another: they represent a light touch that does not want to be permanent, it invites us to reflect and possibly suggest new writings to be projected on the wall that belong to an unknown future rather than being consigned to a past that claims to be eternal.

CONCLUSION: Monuments and Mountains

I visited the Monument to Victory and the permanent exhibition annexed to it many times as part of a study abroad program, an exploration of the Dolomite mountains in Northern Italy, I undertake with groups of students from the University of Oregon. In general, American students reject the monument and its message, some of them, more or less involved with cancel culture, believe that the work of re-contextualization implemented by the permanent exhibition BZ ’18-’45 is insufficient to deal with the past and the fascist message that the monument still represents. However, over the years, I have seen more and more students interested in the attempt trying to rewrite the past and re-contextualize the monument represented by the permanent exhibition. These students become aware of the limits of the cancel culture so widespread in the United States. Over the years I have witnessed multiple attitudes on the part of the local Tyrolean population toward the Monument to Victory. Beyond the obvious differences that oppose the German-speaking population to the Italian one, a widespread perception emerges of the monument as an embarrassing residue of a past that no one is happy to talk about or even to visit.

The work we do in our interdisciplinary study program that tries to combine Earth Sciences and Human Sciences, is to insert the study of the historical monument into a broader temporal perspective, that of the deep time of geology, comparing it with the meaning of the natural monument called Bletterbach, the heart of the Dolomites, twenty five miles away from Bolzano. As the sign at the entrance of the Bletterbach Geopark states, this is a natural monument built over an immemorial time.

While I propose to analyze this natural monument in another post on my blog, I will limit myself here to suggesting that the inclusion of the Victory Monument not only in the regional historical context, but also in that of the regional geological history contributes to further relativizing the meaning and the historical value of the monument which in the intentions of the creators were absolute and timeless. Werner Putzer, our local guide in the Bletterbach gorge in September 2024, found this approach inspiring. He said that he, as many South Tyroleans, had no interest in the Monument to Victory because of the continuous political divisions and violence that it triggered. But, he continued, seen from the perspective of deep time, the Monument to Victory acquired a new meaning, detached from the political battles it inspired in the past. He also mentioned that he wanted to visit the Permanent exhibition, as he understood now the possibility and plausibility to renegotiate the meaning of the historical monument.

Ultimately, one must conclude a post about the possibility of a creative and refreshing ironic gaze on the past by suggesting that the supreme irony directed toward the historical monument is that of nature. Jeffrey Schnapp also directs our attention to this aspect when he concludes his article Small Victories by recalling that recently the Monument to Victory did not make the news for attempts to put sticks of dynamite to destroy it –as happened in the seventies of the last century– but, “when, as occurred on May 4, 2019, slabs of marble came crashing down to the ground. It was nighttime. No one was injured. Even the most enduring temples of historical memory are subject to nature’s higher laws” (Schnapp 2020, 543).

Bibliography

AlexandrIO, Black Lives Matters, Adobe Stock. Education Licence.

Di Michele, Andrea. BZ ’18-’45 : Un Monumento Una Città Due Dittature : Un Percorso Espositivo Nel Monumento Alla Vittoria : Guida Del Percorso Espositivo. Edited by Sabrina Michielli, Morellini : Folio, 2016.

Manzoni, Alessandro. The Betrothed. Trans. Bruce Penman. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972. Print.

Moja, Federico. “Piazza dei Mercanti in Milan with Philip II’s statue,” in Alessandro Manzoni. I Promessi sposi / Storia della Colonna Infame. Milano: Bur, 2014, p.330.

Schnapp, Jeffrey. “Small Victories («BZ ’18–’45»)” The Routledge Companion to Italian Fascist Architecture: Reception and Legacy. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2020, 533-545.

—. “About a monument and a ring,” 23/07/2014, http://jeffreyschnapp.com/tag/monuments/, accessed July 20, 2024.

Soragni, Ugo. “Interview with Ugo Soragni.” BZ ’18-’45. One Monument – One City – Two Dictatorships (Bolzano: Folio, 2016), 24-29.

Thompson, Erin. “The Most Controversial Statue in America Surrenders to the Furnace.” New York Times, Oct. 27, 2023.

Leave a comment